08/11/2021

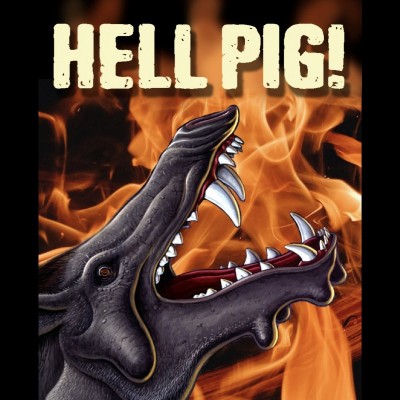

Episode #39 Hell Pigs: T. rex of the Tertiary with Scott Foss

What had giant cheeks, protruding canines, dainty hooves and a giant, ridged back? The Hell Pig is almost like Frankenstein's monster, and Scott Foss tells us all about how these creatures utilized this unique combo of features to be the "T. rex of the Tertiary."

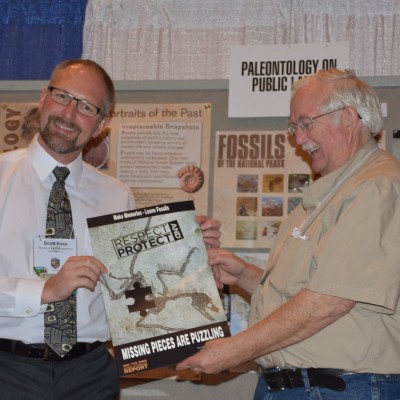

Scott Foss

Division Chief for Education, Cultural and Paleontological Resources at the Bureau of Land Management

Scott knew he wanted to be a paleontologist when he was as young as 2. His kindergarten autobiography even records the very discussion with his grandmother that solidified his career path! Scott's paleontology paragon was the prolific Bob Sloan at the University of Minnesota who prepared him for his life-changing internship at the Badlands National Park (home of the White River Formation). Although Scott faced some rejection when he was looking for a Ph.D. fellowship, he now gets to approve (or deny!) their permits in his current position at the Bureau of Land Management.

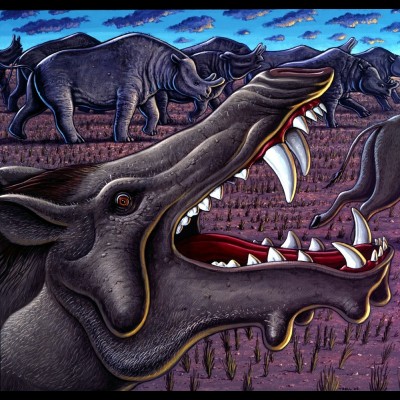

Although their closest extant relatives are pigs, entelodonts (aptly nicknamed "Hell Pigs" and whose name means "Perfect Tooth") are not true pigs. Their niche is somewhere between a bison-sized razorback hog and a grizzly bear. It has bunodont teeth (big flat chewing teeth) like omnivorous humans, rats and bears. Their serrated canines and premolars indicate that they could eat anything, whether they killed it or scavenged it.

The Entelodont family originated in Asia, beginning with Eoentelodon in the Late Eocene. Hell Pigs were top predators until the Early Miocene (17million years ago) with the "Pig Hey Day" being 35-24 million years ago. Early enteleodonts only remain as teeth, so it's difficult to pinpoint exactly when they began evolving the large cheek flanges that are characteristic of later species. The earliest Entelodonts in North America were Brachyhyops, leading the way for Cypretherium and Archaeotherium to continue to develop even larger cheek flanges. Many incredible specimens of Entelodonts came from the Big Pig Dig, the bonebed of stubborn pigs who refused to leave their watering hole as it dried up, scavenging carcasses until they themselves met their demise.

Scott studied the chewing muscles of Entelodonts for his dissertation. The coronoid process (where the jaw connects to the skull) is very low, meaning they can open their mouth very wide, like a hippo. For most animals, being able to open your jaw wide would leave you vulnerable, making it easy for predators to break your jaw. The cheek flanges of Entelodonts allowed them to increase musculature stability and Scott has found evidence that they could withstand a bite to the jaw, often biting each other (presumably as a display of dominance). The flange may also have protected the entelodont's eyes and brain like the hilt of a sword. It's likely that these big pigs were intimidation scavengers, letting other animals kill their prey before scaring them away. So yes, they're pretty cheeky, but for good reason!

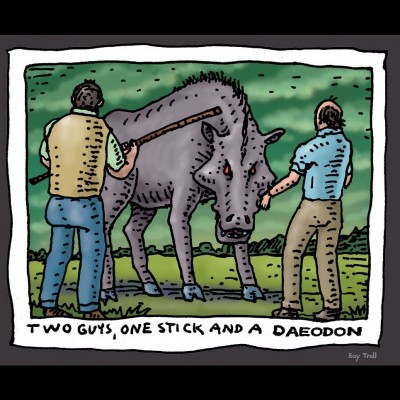

The cheek flanges continue to grow over an individual's lifespan and also evolved bigger and bigger. However, the last (and largest!) Entelodont Daeodon has smaller flanges compared to its predecessors. Scott thinks this is because we haven't found a male Daeodon because females tend to have smaller flanges and perhaps we haven't discovered a fully grown male Daeodon yet.

But could a Hell Pig take on a bear dog? The answer is: they didn't live at the same time. The last Entelodont, Daeodon was long gone before the giant bear dog Amphycyon took over their niche of being the top predator of the Early Miocene.

Ray has channeled his obsession with Hell Pigs into countless drawings, paintings, exhibits and even into song:

Paleo News: The Burgess Shale may be a collection of communities transported by mudslides. Ray is still hoping for melanosomes so he can accurately depict these creatures.

What was that cool song I heard?